Auhorities & Public Mobility Providers

What makes a good business case for public transportation ?

Urban planning

GOOD Mobility is crucial

For a viable city

Urban planning targets to increase the viability of a city, by creating spaces and relations in the urban tissue at the size of human interaction. Urban development needs to enhance the balance between living and working, nature and culture, tranquility and livelyness.

Mobility is a key function in urban planning, since good accessibility is a driver for economy, culture, tourism and social interaction.

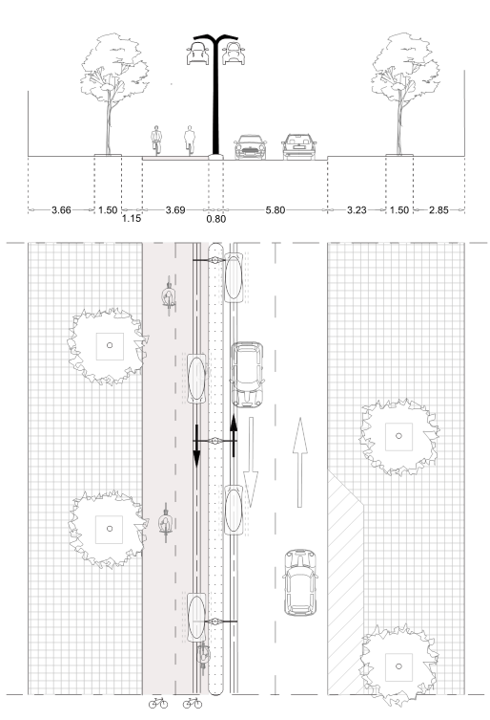

On the other hand, mobility infrastructures occupy over 80% of a city’s public space, leaving little place for other functions. Infrastructure can connect, but can also separate: busy roads are known to create a social barrier between people living on either side of it.

Sustainable urban mobility can vastly improve the overall quality of life for residents by addressing major challenges such as congestion, air/noise pollution, climate change, road accidents, on-street parking and the integration of new mobility services.

Accessibility is a crucial factor in determining the location of a business. When traffic jams and low-car policies reduce the accessibility of the city without a good alternative, businesses will move in 2 directions. Those who can afford it will move towards major public mobility hubs, others will have to move out. The latter will become even more car dependent, but at least they preserve a reasonable accessibility at reasonable real estate prices.

Accessibility is also crucial for customers, tourists and commuters to find their way to the local economy.

Ruling out cars can strongly enhance the viability in a city, but comes at the cost of big investments in public and micro-mobility. These investments are crucial, because the loss of businesses, customers and jobs may cost a multiple.

Shifting the spatial mix form a car-oriented to a micro-mobility oriented model with a separate layer for fast traffic such as FlyByke, will free a lot of space on the ground level. Space that can be used for more interesting functions, such as parks, markets, culture, sports, pedestrian zones, bike lanes, etc. …

New metrics required

How fast a mobility solution is can be specified by stating commercial speed and frequency of the service. In fact the only thing that matters is total travel time (TTT). How long does it take from where I am, to where I want to be?

TTT is not defined between two stops, but between two destinations.

Congestion happens when everybody tries to cross a city at the same peak moment. Conflictless modes – like an underground metro – contribute to decongestioning the city by reducing the traffic on the ground level. We could quantify this with the ratio between the distance travelled on the ground to the total trajectory.

A metro would have GLR 0% (we neglect the pedestrian part of the trip), while cars, busses and trams would have GLR of 100%. FlyByke would only use the ground level for the first and last part of the trip, say a GLR of 5-15% depending on grid density.

A bus or train “Every x minutes” is the way frequency is specified.

What if you don’t have to wait for a vehicle, but there is always a vehicle waiting for you? Frequency becomes infinite and thus irrelevant.

Again, TTT is a more appropriate way to measure performance.

Passenger capacity per vehicle or train is not really relevant. Passenger capacity defined in people per hour per destination will remain a very relevant metric.

Coverage is often defined by the area within 5 min walking distance from a station. Or by the distance between stations. A network with stops every 500 m has a very good accessibility for pedestrians.

In the case of FlyByke, where the vehicle disconnects at the station and continues the trip on the road, the area covered per station is much larger (5 minutes around a station equals a radius of 2 to 3 km ). You can have a better performance with a lower grid density.

So total travel time is a better metric, defining coverage of a network as travel time isochrones starting from specific points of interest.

Service level

Total travel time defines the service level

Grid planning

Local and intercity travel without transfers

Local attraction poles such as shopping areas, historical sites, a commercial district, a campus, a hospital, a market, … need a good disclosure to accomodate vast people flows. These hotspots identify straightforward locations for FlyByke stations.

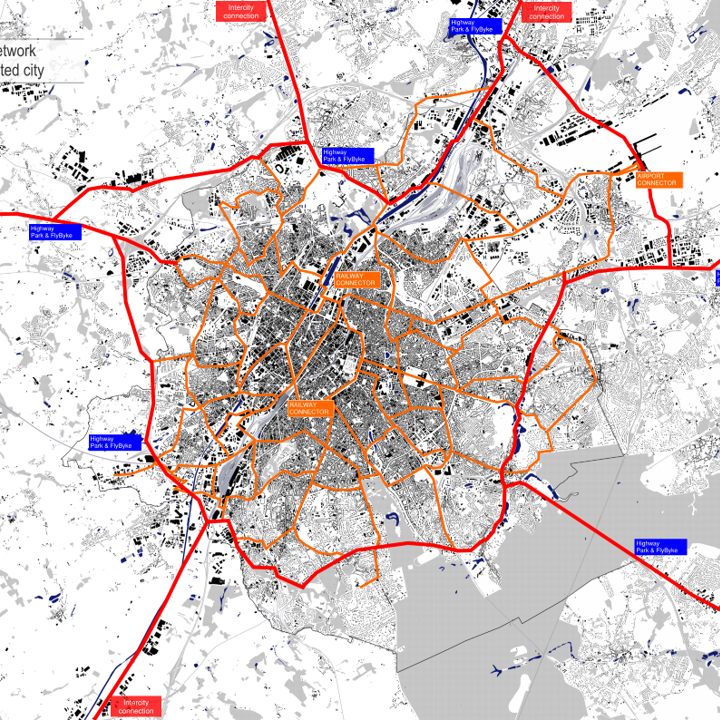

By analysing the current availability of public transportation, missing links in the network can be identified (in time and space). The FlyByke network can complement existing PT solutions by filling in the gaps, increasing the capacity, disclosing new developments or bridging a piece of difficult terrain, a so-called urban fracture.

A new FlyByke network will probaly be developed in phases, starting out with a local connection. Local connections can function as standalone solutions for connecting specific poorly disclosed quarters or new developments to bigger mobility hubs in an environmentally friendly way.

Local connections are the seeds for a broader network.

By meshing local lines and loops into a bigger network, FlyByke will grow to function as a local area network (LAN). A LAN, pretty much like its digital counterpart, will desserve all stations connected to it in a smooth, reliable and 24/7 continuous communication.

Neighbouring cities can connect to an existing FlyByke LAN by intercity extensions of the network. Intercity connections are two-directional tracks at higher speed (130 km/h).

If the second city already had a LAN, the two networks will merge to a bigger one. If not, the new intercity FlyByke station can form the base for building out a new LAN.

Intercity FlyByke stations are no different from local stations. The only difference is the length of the acceleration/deceleration tracks along the main track. An intercity connection will be provided with stations every 2 to 5 kms depending on the forecasted mobility density. A FlyByke intercity track discloses an area of 10 km around it.

Intercity connections are key to achieving an important modal shift away from cars. Once people can hop from city to city in a FlyByke – without tranfers or missed connections – the motivation for taking a car at the risk of being stuck in a traffic jam will be very low.

Just like local connections in the early development stage, local antennas may be built in a later development stage to disclose local town centres, industrial zonings or touristic attractions with a link to the main network.

A regional FlyByke network is the whole of interconnected of LANs, IC-lines and local antennas.

Eventually FlyByke can develop into an internationally connected and fine meshed transportation network.

Mobility hubs are connection points for people to transfer between different mobility modes, such as airports and main railway stations.

Today’s public transportation planning is strongly focused around mobility hubs.

In the future however, mobility hubs will loose their dominance when automatic networks will overtake and tranfers will become a forgotten issue of the past.

FlyByke networks will equally desserve all areas of a city or region.

Real estate developments will no longer be concentrated around a limited number of well accessible places, but can be more evenly spread over the entire region.

FlyByke is multimodal on it’s own. Once a FlyByke network is fully developed, it doesn’t really require connections to other modes (except for long distance high speed trains and flights).

In a first stage of its development however, FlyByke will start as a local area network and will need to connect to existing mobility hubs.

New mobility hubs with large car parks can be created at the outskirts of a city’s main ringroad to specifically stimulate the transfer from cars to FlyByke and other micromobility.

Investments for new public transportation lines are gigantic and weigh heavily on a city’s budget. When mobility becomes profitable this is no longer an issue. Cities can think along with private companies to determine the most profitable business case for their city.

A FlyByke business case covers construction and exploitation for a period of at least 20 years. Based on network lay-out, ridership forecasts and social targets (ride costs), the FlyByke business case can determine the commercial viability of the mobility investment.

For networks on a good location that are naturally profitable, the network can be completely privately financed. In that case the role of public authorities can be focused on a purely facilitating and directing role. If autorities wish to participate in the investment, they are welcome to become shareholder in the project.

In other cases, where ridership is expected to be low or where the government wants to provide cheap rides, public funding may be required to keep the business case viable. Even in that case the tax payer will be winning, since the public investment will be very low in comparison to other mobility solutions.

Business case

Don’t ask what it costs,

but what profit it brings !

Ridership

A better customer experience

will attract more Customers

How many customers can we expect?

New highways attract new vehicles and get congested in 5 years time. When a new PT line is built in a congested city, it is typically at its nominal capacity within half a year. Transportation is a supply-driven market. Investments costs are so high and procedures are so long, that supply can’t keep up with growing demand.

Ridership forecasts will be on the safe side, when we use a new metro line as a reference. Metro lines are seen as the PT with the best service level today, since it’s a conflictless mode with a high frequency (every 2 to 5 mins). We asked people what they would choose for the same trajectory at the same cost: would they travel by FlyByke or with an underground metro line? Most of them choose FlyByke because of street access, shorter TTT and privacy.

When people can choose for a car, they ‘ll do so. Despite all the efforts to discourage car use, the car is still our favourite tranport mode, accounting for over 80 % of our annual person-km’s. If we want to create low-car environments there are two options: bully car users until they give up, or offer something better. FlyByke chooses the second option. We target a modal shift of 20% less cars within 5 years after rolling out the network.

FlyByke can do better than a car. Average car speed on the countryside is typically below 60 km/h and in big city centres below 20 km/h.

FlyByke will have shorter TTT (total travel time) than a car on almost all trajectories.

The comfort is the same.

And it’s ecological !

People will have no more reasons to stick to their car !

(but people will have tendency to do so, that’s why we only target 20% modal shift)

Public authorities play an important role in facilitating the shift towards a low-car environment. Accompanying measures such as a reduction of parking space, low-emission zones, 30km/h areas, allowing for competitive mobility companies, etc. … can favour the growth of micro-mobility, public transportation and FlyByke.

Affordable travel

The cost of traveling is purely economically defined by the cost structure for building, operating, energizing and maintaining the tracks and vehicles, whilst having a reasonable margin at the end of the day to sustain a healthy business.

A tariff is a political choice, taking into account – amongst others – the affordability of travel for less fortunate citizens and the targeted modal shift.

In a 100% private market FlyByke can be profitable with fares based on km-costs of a car and even at the price of public transportation (PT) single ride tickets. If FlyByke is to be offered at fares competitive with current PT annual subscriptions, it will most likely not be profitable, but anyhow require less public money than any other PT solution.

Tariffs

FlYByke is competitive to the cost of a car-KM